How map-making helped spark off the China-India war on the world’s roof

Summary

New Delhi argues—correctly—that the Chinese troops in Pangong or Galwan are on the Indian side of the LAC, which approximates the lines to which the PLA withdrew in 1962.

From the black gravel pass—Karakoram, in the Turkic dialects of the traders who traversed the Himal—Frank Ludlow descended into the Chip-Chap, the silent river, headed to Daulat Beg Oldi, the place where a rich noble had died. From there, the route led to an open plain, Depsang, and then Haji Langar, where a pilgrims to Mecca were fed. Following that was the camp-ground at Burtsé, named for a medicinal shrub. There was one last obstacle before the Galwan river, which climbed through the mountains into the Aksai Chin plateau: Murgo, the gate to hell.

Ludlow’s map, he wrote in his memoirs of his 1928 expedition, showed the location of a safe campsite: “a pile of stones and mud had been erected against the face of a cliff to form a shelter from the wind. I looked inside this shelter and found it contained three skulls and other gruesome human remains”.

A hundred years on, almost, those names mark the frontlines the of still-unfolding confrontation between China and India on the world’s roof. In both countries’ nationalist discourse, each centimetre of this savage mountain terrain is seen as sacred ground—sanctified, as it were, by the blood shed in the 1962 war.

There’s another story to be told, though, about how this conflict came about, and why: a story about how boundaries, and myths, were etched on to maps of lands which had none, as the two great Asian nation-states born in the last century struggled to imagine—and will into being—their borders.

“A team of horses cannot overtake a word that has left the mouth”, observes the novel Journey to the West, counted as one of the four keystones of classical Chinese literature. Nine centuries after the monk Xuanzang journeyed to India and Central Asia to collect the great sutras of Buddhist cannon, his incredible, seventeen-year journey became the foundation of the novel, attributed to Wu Cheng’en. In 1762, a map compiled on the orders of the great Emperor Qianlong was appended to the book, to illustrate the magnificent scale of Xuanzang’s journeys.

The map showed Hindustan lay somewhere south of the Kuen Lun range. The word had been given life: This map would, centuries later, come to form the foundation of India’s claims to Aksai Chin.

From soon after independence, Indian diplomats had become concerned over the slow, westward drift of borders in Chinese maps—a process that had begun long before the communist revolution. Beginning in the 1920s, the Ministry of External Affairs noted in a 1960 document “Chinese maps have departed from the traditional boundary, and included large areas of Indian territory”.

The idea of a traditional boundary, though, wasn’t as uncomplicated as it seems. From the 1850s on imperial British maps had begun to mark the borders of their colony with Tibet, sometimes expanding east and north, as explorers penetrated ever-deeper into the Himalaya. Indian spies like Sarat Chandra Das, Ghulam Muhammad Galwan and Mohan Lal Kashmiri played a key role in this endeavour, posing as mendicants and traders to gather intelligence for the empire.

Few of these regions generated any worthwhile revenue, though. Empire had little interest in asserting territorial control of these lands, leaving their policing to local vassals of regional rulers. For the most part, trade and access to pastures were established by convention, not law, and were—at best—loosely enforced.

Bérénice Guyot-Réchard’s path-breaking scholarship on state-formation in the Himalayas teaches us, moreover, that the populations caught up in these cartographic processes often had no sense of being subjects of either the British or Qing empires—nor involvement in the nationalist projects that would replace them.

ALSO READ | China’s two sessions, multiple decisions

The process of imperial map-making, though, was to have real-world consequences. In 1914, British administrator Henry MacMahon negotiated the borders between India’s north-east and Tibet in Shimla. The border he arrived at—long rejected by China, which argued it had been enforced under duress— drew on the cartographical work of Christian missionaries operating in Tibet in the 1870s.

Kuomintang maps made in the 1930s and 1940s—so worrying to Indian diplomats—were efforts to push back against this imperial cartography, with Chinese nationalist fictions of their own.

Put another way, map-making wasn’t just a reflection of politics or geography: in some key ways, it had begun to shape reality.

Late in 1950, the People’s Liberation Army’s Eighteenth Army marched into Lhasa: a savage crime, in the eyes of some, against small, independent mountain kingdom; a restoration, to others, of land that had been rightfully ruled by China from 1720 to 1911, and lost by a civilisation enfeebled through the Western colonial onslaught. New Delhi, it isn’t widely known, did consider its options: The Foreign Secretary, Director of the Intelligence Bureau and Army chief met amidst calls for Indian military assistance to Tibet.

“The consensus that emerged from that meeting”, India’s war history records, “was that India was in no position whatsoever at that time to intervene militarily”.

Even as New Delhi went along with China’s claims on Tibet, China began survey-work for a road through Aksai Chin in 1951 and announced its completion in six years. The road through the uninhabited plateau was of critical strategic importance to Beijing, allowing to maintain logistics for its garrisons in Tibet through Xinjiang.

“The Indian government”, India’s official history of the war of 1962 admits, “did not come to know of the building of this road as Indian forward posts in this inhospitable and uninhabited region were far behind the map-marked boundary”. Put another way, India believed Aksai Chin to be its own—but had never staked its claim.

In the summer of 1958, Deputy Superintendent of Police Karam Singh and Lieutenant Ram ‘Tiny’ Iyengar headed out into the Aksai Chin, to determine just where the highway ran. Lieutenant Iyengar’s patrol was detected and detained, but Karam Singh’s reconnaissance established the road ran from Haji Langar in the north to Amtogar in the south, cutting some 160 kilometres through Aksai Chin.

Even before these events, there were signs that Beijing wasn’t content with the borders as India understood them. Inside weeks of Prime Minister Chou En-lai’s 1954 visit to India—where he made no suggestion China contested India’s understanding of the border—Beijing protested the presence of the Indian Army on the Barahoti Pass in Uttar Pradesh.

From 1955 on, there was a succession of military intrusions: at Barahoti, the Hipki La in Himachal Pradesh, Kaurik and Hipsang Khud. In each case, China insisted the PLA was on its own territory. Khurnak Fort, in Ladakh, was occupied—and used as a base to supply outposts in Spanggur and Digra.

Then, in 1958, came the map that made those claims explicit: China Pictorial, an official map, asserted claims over the whole of what was then India’s North-East Frontier Agency, with the exception of Tirap, as well as parts of Ladakh, Uttar Pradesh and Himachal Pradesh. Chou En-Lai responded to Indian protests by repeating that the maps were based on old Kuomintang cartography—but added that China hadn’t surveyed its boundaries, nor consulted with other countries on the issue.

Chou En-Lai was to offer a joint survey to delineate the border—but Prime Minister Nehru shot down the proposal outright. “There can be no question about these large parts of India being anything but India”, he wrote on December 14, 1958. “I do not know what kind of surveys can affect these well-known and fixed boundaries”.

The next year, Chou En-Lai offered another deal, proposing both sides withdraw 20 kilometres behind the MacMahon Line in the eastern sector, and a similar distance from their actual ground positions in Ladakh. Feeling this arrangement would cede China control of areas in Ladakh it had occupied, Prime Minister Nehru again rejected the offer.

From June to December 1960, Chinese and Indian officials met in Beijing, New Delhi and Yangon, in a last-ditch effort to hammer out their differences. This time, the Chinese came armed with a Ladakh claim line—or border—running from east of Daulat Beg Oldi, cutting across the Galwan river near its confluence with the Shyok, then to where the Pangong Lake turns north-west, and ending south-west of Demchok. The map was even more expansive than one issued in 1956 and pushed by Chou En-Lai in the 1959 discussions.

Then, in 1959, bloody clashes broke out between the Indian Army and the PLA in the Galwan valley. New Delhi threw its weight behind the so-called Forward Policy: Thinly-held pickets of Indian troops were to assert India’s claims as far ahead as possible, gambling China would not evict them by force. In 1962, that decision backfired.

From Chinese maps issued to the Non-Aligned States in 1962—New Delhi has not issued an official cartographical representation of the war—it’s clear the PLA pushed past the Indian forward posts to its 1960 claim line. Later, it withdrew some 20 kilometres behind that claim line, creating a kind of de-facto no-man’s land.

ALSO READ | What India’s China strategy can learn from a herd of burning, squealing pigs

The rearmament of the Indian Army begun by Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri—and then pushed forward by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi—allowed the Indian Army to begin patrolling the lost territories again. In 1967, a reinvigorated Indian Army beat back Chinese attacks on Nathu La and Cho La, at the gates of the Chumbi Valley—the strategically vital corridor between Bhutan and Sikkim.

Ever since then, an unquiet truce has prevailed along the China-India border. However, since 2013—as India’s road network, logistical infrastructure and defensive fortifications have been enhanced—new pressures have begun to mount.

Fearful that India’s new resources could let it assert—and hold—claims across the 1960 line, the PLA has begun to push back harder. In nine key sectors, Indian patrols have routinely been confronted, leading to a succession of face-offs. This summer’s crisis is the largest seen, in the number of troops it involves, since 1967.

Like in the past, maps have not a little to do with the story: Bar the fact that the Line of Actual Control begins at the Karakoram pass, the two countries agree on few of its details. New Delhi argues—correctly—that the Chinese troops in Pangong or Galwan are on the Indian side of the LAC, which approximates the lines to which the PLA withdrew in 1962. Beijing argues—also correctly—that Indian troops are on its side of the LAC, which approximates its 1960 claim line.

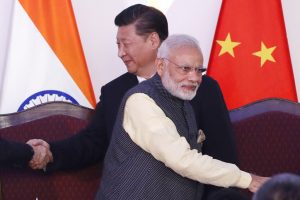

Leaders in both Beijing and New Delhi seem to have concluded, from the successful containment of the multiple crisis since 2013—in which not one shot has been fired—that these are low-risk events. Fuelled by the rising tide of nationalism in both countries, and anger generated by social media images of the clashes, each crisis is placing ever-greater pressures on national leadership—and ever less room for manoeuvre.

“Five kilometres more land we have or five kilometres less—this is not important”, Soviet premier Nikita Khruschev admonished Mao Zedong after the 1959 clashes in India. “I take Lenin’s example, and he gave to Turkey Kars, Ardahan and Ararat. And until today area a part of the population in the Caucasus are displeased by these measures by Lenin. But I believe that his actions were correct”.

That wise counsel wasn’t heard in either New Delhi or Beijing, prisoners of their own maps. Now, the time’s come to start listening.

Elon Musk forms several ‘X Holdings’ companies to fund potential Twitter buyout

3 Mins Read

Thursday’s filing dispelled some doubts, though Musk still has work to do. He and his advisers will spend the coming days vetting potential investors for the equity portion of his offer, according to people familiar with the matter

Listen to the Article

Listen to the Article  Daily Newsletter

Daily Newsletter